My scholarship asks how readers and writers navigate rules for learning, feeling, and speaking. Sometimes such rules stymie creativity; sometimes they provide a fertile ground for artistic appropriation or subversion. Inevitably, however, they point to deeper cultural assumptions about selfhood, belonging, and meaning—assumptions that give us a new vantage point on old literature.

I’m always happy to share offprints, discuss ideas, or answer questions; just email me at spencer.strub [at] princeton.edu.

Articles and Chapters

“The Anchorite as Analysand: Depression and the Uses of Analogy,” Exemplaria 35.1 (2023): 48-65 (available here)

Contemporary scholars sometimes analogize premodern acedia to modern depression, finding promise in ancient therapies for acedia—chiefly forms of bodily activity and mental discipline. This article identifies an alternative model of medieval ascetic therapy in a brief passage in Ancrene Wisse in which a mother playfully hides from her child, who is left to cry alone until she returns and embraces him. The scene, later dubbed “the play of love,” is presented as a similitude illustrating God’s withdrawal from the anchorite, which is experienced as the depressive state known to medieval thinkers as sterilitas mentis. Although it belongs to a long tradition on the benefits of temptation, the play of love also serves an immediate therapeutic end, allowing the anchorite to conceptualize her solitary suffering as part of an ongoing relation with a complex God. The form of the similitude, which facilitates identification across difference, is crucial to this process. Though the play of love operates differently from the therapeutic modes that emerge from other work comparing acedia and depression, it underlines the value of the analogy in the first place, whatever the risks of anachronism.

“Hoccleve, Swelling and Bursting,” in Thomas Hoccleve: New Approaches, ed. Jenni Nuttall and David Watt (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2022), 124-21. (Get the book here! Or view on Cambridge Core.)

This essay focuses on a metaphor for emotional experience that is both entirely conventional in late-medieval poetry and so reflexive and widespread as to be nearly synonymous with the experience itself: the sense that a strong emotion swells, often in the chest, until it bursts out as tears, speech, or even the act of writing. Hoccleve reproduces this metaphor throughout his poetic career, but it enjoys particular pride of place in the Series: the collection begins and ends with swelling and bursting. These moments, defined as they are by their ambivalent relationship to originality — a cliché that nevertheless conveys a embodied particularity — call to mind the question past critics repeatedly posed about the Series: is it a work of fifteenth-century convention, or does it relate an account of experience locatable in the hard facts of a person’s body and brain? Hoccleve’s repertoire of swelling feelings suggests one way in which originality can emerge from the common property of convention. In the Series’s pivotal moments of swelling and bursting, the confrontation between the hard facts of autobiography and warmed-over poetic commonplace renews convention, ‘making it new’ by making it unsettling.

“Oaths and Everyday Life in Peter Idley’s Instructions,” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 119.2 (2020): 190-219 (available here)

Idley’s teaching on oaths and vows is, on the face of things, an uncontroversial treatment of a vexed topic in late medieval religion. The oath is language in extremis—it is a speech act that invokes the sacred, binds the speaking self to its utterance, and inscribes its speaker in a relationship of obligation or accountability—and this perceived power made the value and use of oaths the subject of heated debate among theologians and lay believers. But fifteenth-century business, law, and governance all rested on sworn bonds; oathworthiness was one of the determinative qualities of gentle status. Pastoral theology was therefore obliged to navigate between stringent spiritual directives and a pragmatic accommodation of the practices of secular life. Idley resolves these ambivalences, and secular pragmatism—the worldly demands of gentility—wins out. In doing so, he provides an object lesson in how lay and clerical ethical interests may have genuinely diverged in the later Middle Ages.

“Learning from Shame,” Yearbook of Langland Studies 32 (2018): 37-75 (available on Brepols Online)

This essay addresses the role of shame in Piers Plowman, focusing on Will’s experience of misspeaking and rebuke in passus 11 of the B text. Fourteenth-century devotional writing moralizes shame as the awareness of one’s own sins, or as a collective emotion brought on vicariously by the sins of others or directly by their persecution. In contrast, Will’s shame emerges from the apprehension of his incompletion as a thinking and speaking agent. Rebukes from Scripture and Reason repeatedly cast Will back into a scene of remedial education. As Imaginatif explains, Will’s shame is useful because it breaks, remakes, and teaches. Will’s shame maps a process of learning. Because passus 11 begins where the A text ended, and because Imaginatif connects Will’s shame to his poetic making, this meditation on shame also reflects on the shame and legitimacy of Langland’s lifelong work of revision.

“The Idle Readers of Piers Plowman in Print,” New Medieval Literatures 17 (2017): 201-36 (available on JSTOR)

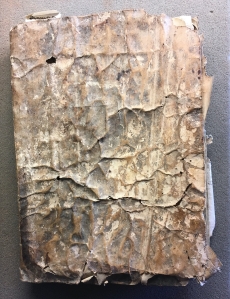

Accounts of Piers Plowman’s early modern reception tend to emphasize antiquarians and Protestant reformers, “readers for action” who used the poem for professional and political ends as an object of study or as evidence for ecclesiological polemic. This article discusses copies of the Crowley and Rogers editions of Piers Plowman now in the Bancroft and Beinecke Libraries, annotated by provincial readers in Derbyshire and Suffolk respectively, in order to articulate an alternative model of reception defined by “idleness” rather than action. The traces left by these “idle readers,” who had no clear professional investment in the poem or its contents, reveal a different way of engaging with the poem: distracted, pleasure-seeking, open to humor and surprise. Their responses suggest that not all early modern readers understood the poem as a useful artifact from a distant medieval past, but could treat it as a living document in their own moment. Because idle readers lack the readily identifiable motivations of reformers and antiquarians, however, they present methodological challenges to critics and book historians. Claims made about them must therefore be tentative and open to uncertainty.

For a full transcription of the annotations in the Bancroft Piers, see here.